Table of Contents

Introduction: The Fog – A Slow, Deceptive Decline

The change was insidious, a fog rolling in so slowly that the 74-year-old man barely noticed the shoreline of his own mind disappearing. It began not with a dramatic event, but with a collection of seemingly disconnected ailments. A dull, persistent headache became his constant companion.1 A profound lethargy settled deep in his bones, transforming simple tasks like walking to the mailbox into monumental efforts.2 Most troubling was the mental haze; he found himself increasingly irritable, his thoughts muddled, and his memory faltering.5

He and his family chalked it up to the inevitable toll of age. After all, he was in his mid-seventies. These symptoms—a little confusion, a bit of weakness, a general feeling of being off-balance that led to a few near-falls—seemed like unfortunate but normal parts of the aging process.6 This misattribution is a common and perilous pitfall. The elderly are a population uniquely vulnerable to the condition that was actually brewing within him. Due to age-related changes in water regulation, the presence of multiple chronic illnesses, and the frequent use of multiple medications (polypharmacy), older adults are at a significantly increased risk for developing dangerously low sodium levels, a condition known as hyponatremia.8 The non-specific nature of its early symptoms means that even mild, chronic hyponatremia is often overlooked, silently contributing to cognitive decline, falls, and even fractures.8

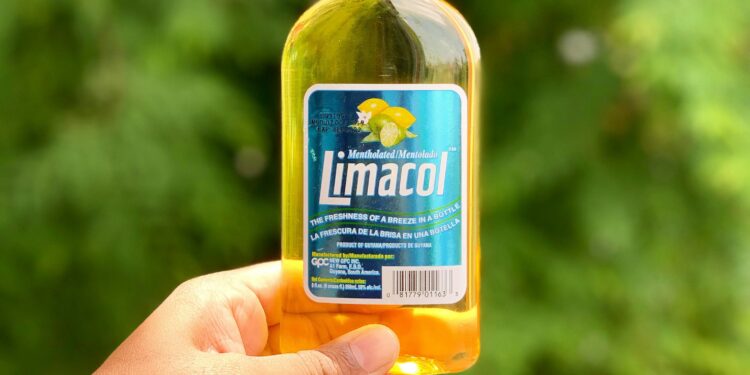

Ironically, the protagonist’s predicament was rooted in his diligent efforts to stay healthy. Concerned about his hypertension, he adhered strictly to a low-salt diet and took his prescribed diuretic—a “water pill”—every morning.11 He also made a point to drink what he believed was a healthy amount of water throughout the day, fearing dehydration.9 Unbeknownst to him, this trio of virtuous habits was creating a perfect storm, systematically diluting the essential salt in his blood and setting the stage for a catastrophic failure.

Part I: The Unraveling – The Body’s Electrical Failure

The slow decline abruptly accelerated into a terrifying spiral. The persistent headache sharpened into a throbbing pain. The nagging nausea intensified, leading to bouts of vomiting.1 His muscle weakness morphed into excruciating cramps and involuntary twitches.4 The mental fog thickened into a dense, disorienting confusion that alarmed his family.7 This escalation of symptoms mirrored a classic progression of worsening hyponatremia, as the body’s internal environment becomes increasingly unstable.13

The crisis reached its apex one evening in his living room. Without warning, his body betrayed him. He experienced a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. His consciousness vanished as every muscle in his body contracted violently, a terrifying spectacle for his family who could only watch helplessly.2 This event was the “ominous sign” that his hyponatremia had transitioned from a chronic ailment into a life-threatening medical emergency, one associated with high mortality if not treated immediately.20

In the chaotic environment of the emergency room, the diagnosis was far from clear. The medical team considered a range of possibilities: a stroke, the sudden onset of epilepsy, a brain tumor. This diagnostic uncertainty is common, as a seizure can be the sole presenting symptom of a severe electrolyte imbalance, masking the true underlying cause.20 After a battery of tests, the bloodwork returned with a critical clue: his serum sodium level was dangerously low.

A neurologist delivered a crucial piece of information that would shape his entire path to recovery. The seizure was not a sign of epilepsy, a chronic condition caused by abnormal electrical activity originating within the brain itself.2 Instead, it was an “acute symptomatic seizure,” an event provoked by an external factor—in this case, the severe metabolic disturbance of low sodium.2 This distinction meant the treatment would not involve long-term anti-epileptic drugs, but would instead focus on correcting the electrolyte imbalance.20 However, a chilling caveat remained: the profound brain swelling caused by severe hyponatremia can, in some cases, lead to permanent brain damage and subsequently trigger the development of epilepsy.2 The race was on not just to save his life, but to preserve his neurological future.

Table 1: The Spectrum of Hyponatremia: From Subtle Signs to a Medical Emergency

| Severity / Sodium Level (mEq/L) | Common Symptoms |

| Mild (130-134) | Nausea, malaise, fatigue, headache, subtle cognitive impairment, increased risk of falls.2 |

| Moderate (125-129) | Worsening headache, lethargy, confusion, muscle weakness, vomiting, forgetfulness.13 |

| Severe (<125) | Obtundation (decreased consciousness), delirium, seizures, coma.11 |

| Critical (<115) | High risk of seizures, respiratory arrest, brain herniation, and death.2 |

Part II: The Diagnosis – Finding the Ghost in the Machine

The turning point came with the arrival of a nephrologist, a specialist in kidney function and electrolyte disorders. The specialist began not with complex medical jargon, but with a simple, powerful analogy to explain the physiological chaos that had led to the seizure. “Imagine your brain is a sponge, perfectly balanced within the salty fluid of your bloodstream. Sodium is the primary salt that maintains this delicate equilibrium. When the fluid outside the sponge becomes too diluted—not enough salt—the fundamental laws of physics, a process called osmosis, force water to move from the blood into the brain cells to try and even out the salt concentration. Your brain cells literally began to swell with excess water”.5

He continued, “But unlike a kitchen sponge that can expand freely, your brain is encased in a rigid, unyielding box: your skull. As the brain swells—a condition called cerebral edema—the pressure inside this closed space builds to catastrophic levels. This intracranial pressure is what caused your worsening headache, the confusion, and ultimately, it disrupted the brain’s normal electrical signaling, triggering a seizure”.1

With the “what” explained, the focus shifted to the “why.” The diagnostic process for hyponatremia has traditionally been challenging. It requires classifying the condition based on the patient’s total body fluid volume—whether they are dehydrated (hypovolemic), fluid-overloaded (hypervolemic), or have a normal fluid volume (euvolemic).4 However, this clinical assessment of volume status is notoriously unreliable, with studies showing that physicians often misclassify patients, leading to incorrect treatment strategies.29 The protagonist’s case was a prime example of this ambiguity; he did not appear obviously dehydrated or edematous.

This is where the specialist introduced a paradigm shift in diagnostic thinking, moving from the subjective art of physical examination to the objective science of biochemistry. “For years, we’ve relied on an educated guess. But now, we have a more precise tool. Your body’s water balance is tightly regulated by a hormone called vasopressin, also known as antidiuretic hormone or ADH.19 It tells your kidneys when to hold onto water. In your case, something was causing your body to release this hormone inappropriately. The problem is, measuring vasopressin directly is technically difficult and unreliable for routine clinical use”.30

“However,” the nephrologist explained, “we’ve discovered that for every molecule of vasopressin released, the body also releases an equimolar, stable, and easily measured partner molecule called Copeptin. Copeptin is a perfect surrogate marker; its level in the blood gives us a clear and accurate picture of what vasopressin is doing”.30

In the protagonist’s case, the Copeptin level, when analyzed in conjunction with his high urine sodium concentration, provided the definitive clue. The combination of these biomarkers accurately differentiates states of true volume depletion from conditions of primary vasopressin release.34 The results pointed unequivocally to the

Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion (SIADH).34 His body was releasing vasopressin when it shouldn’t have been, forcing his kidneys to retain water and dangerously dilute his blood sodium. The most likely trigger for this inappropriate hormonal release was the diuretic medication he had been taking for his hypertension.7 The ghost in the machine had been found.

Table 2: Unmasking the Culprit: Common Causes of Hyponatremia

| Category / Type | Specific Causes and Examples | ||

| Euvolemic / Dilutional (Normal body fluid, but excess water) | Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH Secretion (SIADH): Caused by certain medications (diuretics, antidepressants, some seizure drugs), cancers (especially lung cancer), CNS disorders, or lung diseases.1 | Excessive Water Intake: Includes psychogenic polydipsia (compulsive water drinking) or water intoxication in endurance athletes (marathon runners) or from “water-drinking contests”.38 | Hormonal Changes: Hypothyroidism or adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease).4 |

| Hypovolemic (Loss of both water and sodium, with greater sodium loss) | Gastrointestinal Losses: Severe or chronic vomiting or diarrhea.6 | Renal Losses: Use of diuretic medications (“water pills”) is a very common cause.11 | Other Losses: Significant fluid and electrolyte loss from severe burns.5 |

| Hypervolemic (Gain of both water and sodium, with greater water gain) | Organ Failure: Congestive heart failure, liver cirrhosis, or kidney failure can lead to fluid accumulation that dilutes blood sodium.2 |

Part III: The Tightrope Walk to Recovery – Curing Without Killing

The diagnosis was an epiphany, but the path forward was fraught with a different, more subtle danger. The nephrologist explained the high-stakes nature of the treatment. “We’ve identified the problem, and now we must correct it by raising your blood sodium level. This will pull the excess water out of your brain cells and relieve the pressure. But this is the most critical phase. The cure, if administered incorrectly, can be far more devastating than the initial condition.”

This warning introduced the terrifying prospect of Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome (ODS), a severe and often irreversible neurological injury caused by the treatment itself.42 To illustrate the risk, the specialist offered another analogy. “Over the past weeks, your brain cells have adapted to this flooded, low-salt environment. To keep from bursting, they’ve actively pushed out their own internal solutes and organic osmolytes. They’ve become fragile and accustomed to their waterlogged state. If we raise the salt level in your blood too quickly, it’s like yanking a plant that has adapted to a swamp and dropping it into the middle of a desert. Water will rush

out of these delicate cells so rapidly that they shrivel and self-destruct”.23

“This process,” he concluded gravely, “strips the protective insulation, called the myelin sheath, from the nerves, particularly in a critical relay station in your brainstem called the pons. It can lead to paralysis, a ‘locked-in’ state where you are conscious but unable to move or speak, or even death. This is not a theoretical risk; it is a well-documented consequence of overly aggressive treatment”.42 The gravity of this risk is underscored by numerous medical malpractice cases where patients suffered catastrophic brain injuries or death due to the negligent, over-rapid correction of hyponatremia.15

The recovery process became a tense, meticulous tightrope walk in the Intensive Care Unit. The protagonist was started on an intravenous (IV) infusion of hypertonic saline (3% NaCl), a solution much saltier than normal blood, to slowly and carefully raise his sodium concentration.20 His blood was drawn and analyzed every two to four hours, with the medical team vigilantly tracking the rate of correction.50 The entire process was governed by strict, evidence-based international guidelines that represent a consensus on how to navigate this dangerous therapeutic window. The goal was a slow, controlled rise, adhering to the cardinal rule of hyponatremia correction:

the serum sodium level should not be increased by more than 8-10 mmol/L in the first 24 hours, and by no more than 18 mmol/L over 48 hours.19

As his sodium levels crept back toward the normal range, the fog in his mind began to lift and the physical symptoms abated. The focus then shifted to a new blueprint for life. His diuretic medication, the primary culprit, was discontinued and replaced with an alternative blood pressure therapy. The core of his long-term management plan, however, was fluid restriction.54 He was given a new daily limit of 1.2 liters of total fluid intake and was educated on how to monitor his thirst, read food labels for hidden water content, and track his daily consumption.

Weeks later, back in the quiet of his own home, the protagonist felt a clarity he hadn’t realized he had lost. The headaches were gone, his energy had returned, and his thoughts were sharp. He had survived not one, but two distinct threats: first, the life-threatening brain swelling from too little salt, and second, the potentially catastrophic neurological damage from a too-rapid cure. His experience serves as a profound testament to the body’s delicate chemical balance and a stark warning that even seemingly benign symptoms, especially in older adults, can signal a silent, gathering storm.

Table 3: The Tightrope of Treatment: A Summary of Hyponatremia Correction Guidelines

| Scenario | First-Line Treatment (US & European Consensus) | Key Recommendation: Safe Correction Rate | Rationale / Warning | ||

| Acute / Severely Symptomatic Hyponatremia (e.g., seizures, coma) | Immediate bolus infusion of 3% hypertonic saline (e.g., 100-150 mL over 10-20 minutes, repeated as needed).52 | Goal: Initial rise of 4-6 mmol/L to alleviate severe neurological symptoms.57 | To rapidly reverse life-threatening cerebral edema and prevent brain herniation.20 | ||

| Chronic / Mild-Moderate Hyponatremia | For SIADH / Hypervolemia: Fluid restriction (e.g., <1.2 L/day).55 | For Hypovolemia: Isotonic (0.9%) saline infusion.52 | LIMIT: Do not exceed 8-10 mmol/L in the first 24 hours.50 | LIMIT: Do not exceed 18 mmol/L in the first 48 hours.19 | To prevent irreversible neurological damage from Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome (ODS), a condition caused by the brain cells dehydrating too quickly.42 |

| Management of Overcorrection (Rate exceeds safe limits) | Stop active sodium infusion. Consider administering hypotonic fluids (e.g., 5% dextrose in water) and/or desmopressin (a synthetic form of ADH) to re-lower sodium levels carefully.47 | N/A | To actively reverse the rapid osmotic shift and mitigate the risk of ODS.52 |

Sources: Based on guidelines and recommendations from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the European Society of Endocrinology, and expert consensus panels in the United States.52

Works cited

- pathophysiology and treatment of hyponatraemic encephalopathy …, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article/18/12/2486/1815487

- Hyponatremia seizure overview – why does it happen? – Epsy Health, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.epsyhealth.com/seizure-epilepsy-blog/hyponatremia-seizure-overview—why-does-it-happen

- Hyponatremia: Why Low Sodium Levels Are Dangerous | University Hospitals, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.uhhospitals.org/blog/articles/2024/11/hyponatremia-why-low-sodium-levels-are-dangerous

- Hyponatremia: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment – Cleveland Clinic, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17762-hyponatremia

- Low blood sodium: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000394.htm

- Hyponatremia (Low Level of Sodium in the Blood) – Hormonal and Metabolic Disorders, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/hormonal-and-metabolic-disorders/electrolyte-balance/hyponatremia-low-level-of-sodium-in-the-blood

- SIADH (Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion) – Cleveland Clinic, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23976-siadh-syndrome-of-inappropriate-antidiuretic-hormone-secretion

- Hyponatremia: Special Considerations in Older Patients – MDPI, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/3/3/944

- Hyponatremia in the elderly: challenges and solutions – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5694198/

- Hyponatremia in the Elderly: Risk Factors, Clinical Consequences, and Management | Consultant360, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.consultant360.com/articles/hyponatremia-elderly-risk-factors-clinical-consequences-and-management

- Low blood sodium in older adults: A concern? – Mayo Clinic, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hyponatremia/expert-answers/low-blood-sodium/faq-20058465

- Low Levels of Sodium in the Elderly – Signs, Symptoms &… – SureSafe – Personal Alarms, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://personalalarms.org/blog/elderly-care/low-levels-of-sodium-in-the-elderly

- What are the symptoms of hyponatremia (low sodium levels)? – Dr.Oracle AI, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.droracle.ai/articles/232674/symptoms-of-hyponatremia

- Loop diuretic-induced hyponatremia: a case report, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ijbcp.com/index.php/ijbcp/article/view/241

- Hyponatremia Case Review – ACEP, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.acep.org/life-as-a-physician/ethics–legal/standard-of-care-review/hyponatremia-case-review

- Can You Drink Too Much Water? | University Hospitals, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.uhhospitals.org/blog/articles/2024/01/can-you-drink-too-much-water

- EXERCISE-ASSOCIATED HYPONATREMIA – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6735969/

- Hyponatremia – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hyponatremia/symptoms-causes/syc-20373711

- Hyponatraemic Seizures – Metabolic Muddle – LITFL, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://litfl.com/hyponatraemic-seizures/

- Acute Symptomatic Seizures Caused by Electrolyte Disturbances – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4712283/

- Acute Symptomatic Seizures Caused by Electrolyte Disturbances – PubMed, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26754778/

- Clinical Practice Guidelines : Hyponatraemia – The Royal Children’s Hospital, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/hyponatraemia/

- Hyponatremia and the Brain – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5762960/

- Adaptation of the Brain to Hyponatremia and Its Clinical Implications – MDPI, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/5/1714

- Cerebral Oedema – Physiopedia, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Cerebral_Oedema

- Hyponatremia – Wikipedia, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyponatremia

- Cerebral Edema – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537272/

- Hyponatremia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470386/

- Hyponatremia – Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders – Merck Manual Professional Edition, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/electrolyte-disorders/hyponatremia

- The use of copeptin, the stable peptide of the vasopressin precursor, in the differential diagnosis of sodium imbalance in patients with acute diseases | Swiss Medical Weekly, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://smw.ch/index.php/smw/article/view/1356/1597

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyponatremia: Compilation of the Guidelines. – SciSpace, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://scispace.com/pdf/diagnosis-and-treatment-of-hyponatremia-compilation-of-the-49n6hhz39n.pdf

- medlineplus.gov, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000314.htm#:~:text=Syndrome%20of%20inappropriate%20antidiuretic%20hormone%20secretion%20(SIADH)%20is%20a%20condition,to%20retain%20too%20much%20water.

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507777/

- Copeptin in the Differential Diagnosis of Hyponatremia | The Journal …, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/94/1/123/2597856

- Approach to the Patient: “Utility of the Copeptin Assay” – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9113794/

- (PDF) Copeptin in the differential diagnosis of hyponatremia – ResearchGate, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224929519_Copeptin_in_the_differential_diagnosis_of_hyponatremia

- Reassessing the Role of Copeptin in Emergency Department Admissions for Hypotonic Hyponatremia | The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism | Oxford Academic, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jcem/advance-article/doi/10.1210/clinem/dgaf266/8124474

- Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572128/

- Water Intoxication: Current Developments In Hyponatremia – The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2075&context=student_scholarship

- Fatal water intoxication – PMC, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1770067/

- Management of Hyponatremia | AAFP, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2004/0515/p2387.html

- Central Pontine Myelinolysis (CPM): Causes & Treatment – Cleveland Clinic, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22445-central-pontine-myelinolysis-osmotic-demyelination-syndrome

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://radiopaedia.org/articles/osmotic-demyelination-syndrome

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome following slow correction of hyponatremia: Possible role of hypokalemia – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3796902/

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome and thoughts on its prevention – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8803789/

- Understanding Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome as a Birth Injury – Hampton & King, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.hamptonking.com/blog/understanding-osmotic-demyelination-syndrome-as-a-birth-injury/

- Central Pontine Myelinolysis – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551697/

- Hyponatremia Medical Malpractice Lawsuit – Lupetin & Unatin, LLC, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.pamedmal.com/hyponatremia-medical-malpractice-lawsuit/

- 3% Hypertonic saline – BCEHS Handbook, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://handbook.bcehs.ca/drug-monographs/3-hypertonic-saline/

- What are the treatment guidelines for hyponatremia? – Dr.Oracle AI, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.droracle.ai/articles/195206/what-are-the-treatment-guidelines-for-hyponatremia

- The Resuscitationist’s Approach to Severe Hyponatremia | Critical Care Medicine Section, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.acep.org/criticalcare/newsroom/newsroom-articles/september2022/the-resuscitationists-approach-to-severe-hyponatremia

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyponatremia: Compilation of the …, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5407738/

- What is the safe rate of sodium correction for hyponatremia (low sodium levels)?, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.droracle.ai/articles/40771/how-much-is-it-safe-to-increase-sodium-for-hyponatremia

- pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3183532/#:~:text=Fluid%20restriction%20is%20the%20main%20stay%20of%20treatment%2C%20especially%20in,less%20than%20800%20mg%2Fday.

- The suspect – SIADH – RACGP, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2017/september/the-suspect-siadh

- Do patients with Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone (SIADH) require fluid restriction in the hospital? – Dr.Oracle AI, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://droracle.ai/articles/65524/do-patients-with-syndrome-of-inappropriate-antidiuretic-hormone-siadh-require-fluid-restriction-in-the-hospital

- Hypertonic Saline for Hyponatremia: Meeting Goals and Avoiding Harm – PMC, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10332848/

- SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY ENDOCRINE EMERGENCY …, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://ec.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/ec/5/5/G4.xml

- Emergency management of severe and moderately severely symptomatic hyponatraemia in adult patients – Society for Endocrinology, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.endocrinology.org/media/xhrhxhxm/emergency-management-of-severe-and-moderately-severely-symptomatic-hyponatraemia-in-adult-patients-2022.pdf

- Principles of Management of Severe Hyponatremia – American Heart Association Journals, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/jaha.112.005199

- Diagnosis and Management of Sodium Disorders: Hyponatremia …, accessed on August 14, 2025, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2015/0301/p299.html