Table of Contents

Introduction: The Chef’s Awakening

For Chef Duane Sunwold, a culinary arts instructor, flavor was the language of his life and career.

Salt, in its myriad forms, was a fundamental part of its grammar—a tool to enhance, preserve, and transform.

His diagnosis with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) presented a cruel paradox, a high-stakes conflict where the very instrument of his craft had become a threat to his existence.

This was not merely a dietary suggestion; it was a mandate that struck at the core of his identity.

Yet, in a testament to the transformative power of knowledge and will, Chef Sunwold embarked on a journey that led him to reinvent his relationship with food, ultimately putting his disease into remission by fundamentally changing his diet and adhering to his doctor’s recommendations.1

His story, dramatic and deeply personal, is a powerful metaphor for the journey millions of individuals with kidney disease undertake.

It is a path that begins with the shock of diagnosis and the daunting prospect of a life of restriction, but it can lead to a place of profound empowerment.

This report frames the intricate relationship between sodium and kidney function not as a dry academic exercise, but as a critical map for this transformative journey.

It posits that by understanding the delicate biological dance within our bodies, patients can evolve from passive recipients of dietary rules into active, knowledgeable architects of their own well-being.

The story of salt and the kidney is, ultimately, a story of re-education, adaptation, and the rediscovery of health.

Section 1: The Body’s Master Regulator: How Kidneys Command the Sodium Seas

To comprehend the stakes of a low-sodium diet in kidney disease, one must first appreciate the elegance and complexity of the healthy kidney.

Far from being a simple filter, the kidney functions as the body’s master homeostatic regulator—a highly sophisticated, self-regulating water purification and resource management plant.2

This biological marvel doesn’t just discard waste; it meticulously manages the composition of the body’s internal “ocean,” the vast pool of extracellular fluid, ensuring its stability for life itself to thrive.

The Science of Homeostasis

At the heart of this regulation is the maintenance of a physiological “set point” for sodium concentration in the blood.

This target value, a dynamically defended range typically between 135 and 145 millimoles per liter (mmol/L), is critical for the normal function of nerves and muscles and for the overall balance of fluids in the body.4

The body’s entire regulatory apparatus works tirelessly to keep sodium within this narrow window.

This process is governed by negative feedback loops, analogous to a household thermostat that activates the furnace when the temperature drops and the air conditioner when it rises.6

When blood sodium levels deviate from the set point, the kidneys initiate a cascade of complex processes to restore balance.

Blood pressure, a key variable in this system, can be understood through a hydraulic analogy: it is the pressure within the “pipes” of the circulatory system, a force essential for driving filtration through the kidneys.

When this pressure becomes chronically elevated, however, it can inflict significant damage on the delicate filtration units.7

The sheer intricacy of the interplay between hormones, signaling pathways, and specialized transporters reveals a system designed for exquisite, fine-tuned control.

This is not basic plumbing; it is a form of biological computation, constantly processing inputs like dietary sodium and executing complex algorithms to maintain a stable internal state.

The Molecular Machinery

The kidney’s regulatory power is executed by a team of molecular and hormonal players working in concert:

- The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): This can be viewed as the plant’s “emergency response system.” When the kidneys sense a drop in blood flow or sodium levels, they release an enzyme called renin. This triggers a cascade that culminates in the production of angiotensin II and aldosterone. Angiotensin II constricts blood vessels to raise blood pressure, while aldosterone signals the kidneys to retain more sodium and water, thereby increasing blood volume and pressure.8 In CKD, this system can become inappropriately activated, contributing to persistent hypertension.10

- Vasopressin (Antidiuretic Hormone – ADH): This hormone acts as the “water conservation manager.” Released from the pituitary gland in response to high sodium concentration or low blood volume, vasopressin travels to the kidneys and instructs them to reabsorb more water back into the body.11 It achieves this by stimulating the insertion of specialized water channels, known as aquaporin-2 (AQP2), into the membranes of kidney cells. This process makes the kidney’s collecting ducts more permeable to water, allowing for its conservation and the production of more concentrated urine.11

- Key Transporters (The Workers): The actual work of moving sodium ions across the kidney tubules is performed by a host of protein transporters. Two of the most critical are the Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) and the Sodium-Chloride Cotransporter (NCC). These transporters are the “workers” on the nephron’s reabsorption assembly line. Hormones like aldosterone directly influence the activity and number of ENaC channels, while other complex signaling pathways involving kinases like SPAK and WNKs regulate the activity of NCC.12 The coordinated regulation of these transporters, influenced by everything from hormones to sympathetic nerve activity, allows the kidney to precisely control how much sodium is returned to the blood versus how much is excreted in the urine. This intricate network of cross-talking systems underscores a level of sophistication far beyond that of a simple filter, revealing the kidney as a dynamic and intelligent regulatory organ.

Section 2: When the Balance Fails: The Twin Perils of Sodium Dysregulation in CKD

Chronic Kidney Disease fundamentally damages the body’s “purification plant,” crippling its ability to manage sodium and water.

The failing kidney loses its operational flexibility, its capacity to adapt to the normal fluctuations of daily life.

It becomes unable to effectively handle either an excess or a deficit of sodium, placing the body on a precarious knife’s edge.11

This loss of regulatory range is the core failure in advanced CKD, transforming the patient’s body into a fragile ecosystem where small deviations in diet or fluid intake can trigger disproportionately severe consequences.

This explains why the “renal diet” is so rigidly controlled—it is an attempt to manually impose the stability the kidneys can no longer provide on their own.

Part A: The Flood – Hypervolemia and Hypertension

The most common and direct consequence of high sodium intake in the context of CKD is a dangerous buildup of fluid.

When the kidneys cannot excrete excess dietary sodium, the body retains water to maintain the proper sodium concentration in the blood.

This leads to an increase in the total volume of fluid in the body, a condition known as hypervolemia.8

This fluid overload initiates a vicious cycle.

The excess volume in the bloodstream directly increases blood pressure (hypertension).8

This sustained high pressure then acts as a relentless toxin, inflicting further damage on the delicate blood vessels and filtering units (glomeruli) within the already compromised kidneys.

This additional damage further reduces the kidneys’ ability to excrete sodium and water, which in turn worsens the fluid overload and hypertension, creating a devastating feedback loop that accelerates the progression of the disease.17

For the patient, this internal “flood” has painful and frightening physical manifestations.

The excess fluid leaks out of the bloodstream and into the body’s tissues, causing edema—visible swelling in the legs, ankles, hands, and face.16

When the fluid accumulates in the lungs, it can cause severe shortness of breath, a condition known as pulmonary edema.19

For patients on dialysis, this fluid overload between treatments can lead to uncomfortable cramping, dangerous drops in blood pressure during the dialysis session, and increased strain on the heart.1

Part B: The Drought – The Paradox of Hyponatremia

Paradoxically, the same failing kidneys that struggle with fluid overload can also lead to a condition of low blood sodium, or hyponatremia, defined as a serum sodium level below 135 mEq/L.5

This condition is a common and dangerous electrolyte abnormality in patients with advanced CKD.11

It is crucial to understand that in this context, hyponatremia is most often a

dilutional problem.

It is not caused by a true deficit of sodium from the diet, but rather by an excess of total body water relative to the body’s total sodium content.

The kidneys’ inability to excrete free water effectively “waters down” the blood, making the sodium concentration appear low.4

The symptoms of hyponatremia can range from mild nausea, headache, and fatigue to severe confusion, seizures, and even coma in acute cases.4

The management of severe hyponatremia in CKD patients presents a profound clinical challenge.

Over time, the brain adapts to the low-sodium environment.

If the blood sodium level is corrected too quickly—for instance, during a standard hemodialysis session—it can trigger a catastrophic neurological condition known as Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome (ODS).

This rapid shift in osmolarity pulls water out of brain cells too fast, causing irreversible damage to the protective myelin sheath around nerve fibers.11

To avert this danger, clinicians must walk a tightrope.

The standard of care involves a cautious and gradual correction of serum sodium.

This may involve an initial slow intravenous infusion of a concentrated salt solution (hypertonic saline) with a strict target to raise the sodium level by no more than 8-12 mmol/L in the first 24 hours.

Only after the sodium level has been safely raised to a less critical level is hemodialysis initiated, often using a specially formulated dialysate with a lower-than-usual sodium concentration to prevent abrupt shifts.20

This painstaking process highlights the precarious balance that must be maintained when the body’s master regulator can no longer perform its duties.

Section 3: Navigating the Salt Maze: The “J-Curve” and the Search for Truth

In the vast landscape of nutritional science, few topics have generated as much public confusion as the role of dietary sodium.

This confusion is epitomized by the “J-shaped curve” hypothesis.

This theory posits that while high sodium intake is clearly associated with poor health outcomes, very low sodium intake might also increase cardiovascular risk, creating a J-shaped curve where the lowest risk lies at a moderate level of consumption.8

Proposed mechanisms for this purported harm at low intakes include the activation of the RAAS and sympathetic nervous systems, as well as potential increases in insulin resistance.25

This debate, however, represents a case study in the misapplication of general population data to a specific clinical group.

For patients with CKD, the “controversy” is largely a distraction from a clear and evidence-based therapeutic mandate.

The scientific discourse must always ask a critical question: in which population was this evidence generated, and does it apply here? The physiological context of a person with healthy kidneys is fundamentally different from that of a CKD patient, who is known to be particularly “salt sensitive”—meaning their blood pressure responds far more dramatically to changes in sodium intake.8

Deconstructing the Evidence

A critical look at the research reveals why the J-curve hypothesis is not applicable to the CKD population.

- Methodological Flaws: Many observational studies that report a J-curve in the general population suffer from significant methodological weaknesses. A primary issue is the use of single, spot urine samples to estimate sodium intake, a method that is notoriously unreliable for assessing an individual’s long-term dietary habits compared to the gold-standard of multiple 24-hour urine collections.23 Furthermore, these studies are plagued by the risk of “reverse causation”—the possibility that individuals who are already sick (e.g., with heart failure or other chronic conditions) may have a poor appetite and thus eat less salt. In this scenario, the underlying illness, not the low salt intake, is the cause of the poor outcome, but it creates a statistical illusion that low sodium is harmful.28

- The Strength of CKD-Specific Evidence: In stark contrast to the murky data from the general population, the evidence from studies conducted specifically in patients with CKD is robust, consistent, and compelling. A meta-analysis of multiple epidemiological studies concluded that higher sodium intake is significantly associated with an increased risk of developing CKD.30 More importantly, high-quality, double-blind, randomized controlled trials—the highest standard of medical evidence—have been conducted in patients with moderate-to-severe CKD. These trials powerfully demonstrate that restricting dietary sodium leads to clinically significant and important reductions in blood pressure, proteinuria (excess protein in the urine, a key marker of kidney damage), and extracellular fluid volume.27 These are not just changes in numbers; they are improvements in key risk factors known to slow the progression of kidney disease and reduce cardiovascular events.

The Verdict for Patients

For individuals with CKD, hypertension, or both, the scientific verdict is clear.

The theoretical J-curve, derived from flawed data in dissimilar populations, should not be a source of confusion or a reason to deviate from medical advice.

The overwhelming weight of high-quality, population-specific evidence supports dietary sodium restriction as a cornerstone of management.9

This intervention is not a matter of debate but a proven strategy to protect kidney function, control blood pressure, and improve overall health.

Section 4: The Renal Diet Revolution: A Practical Guide to Low-Sodium Living

The command to “eat less salt” can feel like a life sentence of bland food and constant vigilance.

Yet, for many, this restriction becomes the catalyst for a culinary revolution.

It is a journey from a mindset of deprivation to one of creativity, a challenge to rediscover flavor beyond the salt shaker.

This transformation is embodied in the stories of patients like Chef Duane Sunwold, who had to deconstruct and rebuild his entire professional understanding of flavor 1, and Lori, a patient who initially felt her world had ended but eventually found joy in exploring the grocery store for new, healthy options.37

This section provides the practical blueprint for that journey, moving from the “why” of sodium restriction to the “how” of low-sodium living.

The Low-Sodium Blueprint

The first step is understanding the targets and the tools.

While individual needs vary, general guidelines from organizations like the National Kidney Foundation recommend that people with CKD limit their sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg per day.

For those who also have high blood pressure, a stricter goal of 1,500 mg per day is often more appropriate.1

- Mastering the Food Label: The Nutrition Facts label is the single most important tool. It is essential to look beyond marketing claims and focus on the numbers. Pay attention to the serving size, as the sodium content listed is per serving. A key rule of thumb is to choose foods with a sodium content of 5% to 10% of the Daily Value (% DV) or less per serving.1 Terms on the front of the package have specific meanings: “sodium-free” means less than 5 mg per serving, while “low-sodium” means 140 mg or less per serving. “Reduced-sodium” simply means 25% less than the original product, which could still be a high-sodium food.1

- The 75% Problem: A critical realization for anyone starting this journey is that the salt shaker is not the main culprit. Approximately 75% of the sodium in the average diet comes from processed foods and restaurant meals, added long before the food reaches the table.40 This insight correctly shifts the battleground from the dining room to the grocery store aisle and the home kitchen.

- Avoiding Hidden Sodium and Traps: Sodium hides in many unexpected places. The most common offenders include processed and cured meats (bacon, deli meats), canned soups and vegetables, frozen dinners, condiments (ketchup, soy sauce), and salty snacks.16 Even fresh poultry is often injected with a saltwater solution, or brine, to enhance juiciness, significantly increasing its sodium content.1 A particularly dangerous trap for kidney patients is the use of “low-sodium” salt substitutes. Many of these products, such as LoSalt®, replace sodium chloride with potassium chloride. For a CKD patient who must also limit potassium, these substitutes can be extremely hazardous.16

The Flavor Arsenal

Learning to cook with less salt is about learning to build flavor with other ingredients.

The new flavor arsenal includes:

- Herbs and Spices: A world of flavor exists in the spice rack. It is vital to choose powders (like garlic powder or onion powder) instead of salts (garlic salt). Pre-made spice blends like Mrs. Dash® are specifically designed to be salt-free.43

- Acids: Bright, acidic ingredients can mimic the flavor-enhancing quality of salt. A squeeze of fresh lemon or lime juice, or a splash of vinegar, can awaken the flavors in a dish.39

- Aromatics: Building a flavor base with fresh aromatics is a classic culinary technique. Sautéing fresh garlic, onions, ginger, celery, and peppers in a little oil creates a deep, savory foundation for any meal.43

- Homemade Stocks and Sauces: Preparing stocks, broths, and tomato sauces from scratch puts you in complete control of the sodium content. These can be made in large batches and frozen for convenient use.1

Reframing dietary change from a negative list of what is forbidden to a positive list of what can be enjoyed instead is a powerful psychological tool.

It provides immediate, actionable solutions to common challenges and fosters a sense of agency and possibility, which is crucial for long-term success.

Table 1: The Low-Sodium Swap Sheet for the Renal Kitchen

| High-Sodium Trap | Kidney-Friendly Swap |

| Canned Soup | Homemade soup made with no-salt-added stock or broth. |

| Processed Deli Meat (Ham, Bologna) | Freshly roasted and sliced chicken or turkey breast; unsalted canned tuna. |

| Frozen Pizza / Frozen Dinners | Homemade flatbread pizza with low-sodium sauce and cheese; batch-cooked homemade meals. |

| Salty Snacks (Chips, Pretzels) | Unsalted popcorn, unsalted nuts and seeds, fresh vegetable sticks (carrots, cucumbers, peppers). |

| Bottled Salad Dressing | Homemade vinaigrette with olive oil, vinegar, and herbs. |

| Soy Sauce / Teriyaki Sauce | Low-sodium soy sauce in moderation, or coconut aminos for a soy-free, lower-sodium alternative. |

| Table Salt / Garlic Salt / Onion Salt | Salt-free seasoning blends (e.g., Mrs. Dash®), garlic powder, onion powder, fresh herbs. |

| Salted Butter | Unsalted butter for cooking and baking. |

| Regular Canned Vegetables/Beans | No-salt-added canned versions, or fresh/frozen options. Rinsing regular canned goods can remove some sodium. |

| Commercial Bread and Cereals | Breads with lower sodium content (check labels); puffed rice or wheat cereals. |

Sources: 16

Section 5: The Human Element: From Diagnosis to Empowerment

Beyond the blood tests and dietary charts lies the profound human experience of living with a chronic illness.

Successful long-term management of CKD is a tripartite achievement, requiring not just clinical intervention and patient adherence, but also a fundamental psychological reframing of one’s relationship with the disease and the lifestyle it necessitates.

The journey is not merely about following rules; it is a transformation from seeing the diet as an external punishment to embracing it as an internal tool of self-care and empowerment.

The most meaningful success stories are measured not just in improved lab numbers, but in a reclaimed sense of control over one’s life.

The Emotional Rollercoaster

For many, the journey begins with a shockwave.

Lori, a patient who shared her story, recalls the moment a dietitian explained the new rules of her life after a diagnosis of end-stage renal failure.

“I was shocked and devastated,” she said.

“I felt like the world had come to the end”.37

This feeling of being overwhelmed by a long list of forbidden foods is a near-universal experience, a grief for a life and a palate that have been irrevocably lost.37

The turning point often comes with a hand reaching out in the darkness.

For Lori, it was a renal dietitian, June Martin, who came to her home and offered not just rules, but solutions.

For Katja Hansen, a patient managing both CKD and diabetes, it was her transplant team recommending the PATH (Personal Action Toward Health) program, a support group that provided strategies and, crucially, a community of peers.37

These encounters underscore the indispensable role of renal dietitians and support programs.

They provide personalized guidance, practical tips, and the emotional support needed to navigate the initial chaos.19

The Journey of Adaptation

With guidance and support, the slow process of adaptation begins.

It is a journey marked by small, confidence-building victories.

Lori, a cheese lover, was devastated at the thought of giving it up, until her dietitian pointed out that brie cheese is lower in phosphorus, offering a permissible indulgence.37

This small piece of information was a lifeline.

The journey continued in the grocery store aisles, which transformed from a landscape of temptation and restriction into a place of discovery.

Lori stumbled upon a no-salt-added pasta sauce, allowing her to enjoy one of her favorite meals again.

She learned that the diet “doesn’t always mean that you have to totally ‘give up’ some foods if you are able to find a low-sodium product”.37

This adaptation can even lead to unexpected positive changes.

Lori realized that by cutting out her daily cans of Coca-Cola and Iced Tea—both sources of sugar and fluid—she began to lose weight and feel better.37

For some, taste perceptions even change over time, and foods once disliked become enjoyable.37

Achieving Empowerment

The culmination of this journey is a profound shift in mindset.

Lori, who once hated grocery shopping, now finds it a “fun experience” and enjoys the hunt for healthier foods.37

Katja, after participating in her PATH workshop, felt a surge of confidence.

“I was so surprised at how good it felt to just talk with other people who have the same disease,” she recalled.

“Taking the classes and listening to others’ experiences has been very empowering.

This actually helped me to live with it easier and feel like I can do this”.46

This is the destination: a state of empowerment where the patient is no longer a victim of their diagnosis but an active, knowledgeable, and confident manager of their own health.

They learn to “think outside the box,” to experiment in the kitchen, and to take pride in a lifestyle that sustains them.

It is the realization that, as Katja put it, “healthy food can make a difference”.46

Conclusion: The Future is Personal

The intricate dance between sodium and the kidneys is a fundamental rhythm of life.

We have journeyed from the awe-inspiring complexity of the healthy kidney’s regulatory systems to the devastating consequences that unfold when that system fails.

The evidence is unequivocal: for individuals with Chronic Kidney Disease, the careful management of dietary sodium is not a lifestyle preference but a medical necessity, a powerful intervention proven to slow disease progression and protect cardiovascular health.

The stories of patients like Chef Duane, Lori, and Katja illuminate the path from the initial shock of diagnosis to a place of empowerment, demonstrating that a life of restriction can be transformed into a life of creative, health-affirming choices.

As we look to the horizon, the evolution of this journey continues.

The future of nephrology nutrition is one of increasing personalization.48

While current guidelines provide an excellent and life-saving foundation, the one-size-fits-all approach of a single sodium target for all patients is beginning to give way to a more nuanced paradigm.

Emerging research into “multi-omics”—the integrated analysis of an individual’s unique genetic, metabolic, and microbial profiles—promises to one day allow for dietary recommendations tailored with remarkable precision.48

This future approach will consider not only a patient’s comorbidities but also their unique biology and even their socio-cultural preferences to craft a nutritional plan that is both maximally effective and truly sustainable.

This evolution from a generic, restrictive diet to a personalized, creative way of eating mirrors the progress of medicine itself.

The future holds the promise of ever more precise tools.

Yet, the fundamental power to learn, to adapt, and to take control of one’s own health is not a distant dream; it is available to patients today.

The journey is challenging, but as countless individuals have shown, the destination—a healthier, more vibrant, and empowered life—is worth every single step.

Works cited

- How Much Sodium Is Safe for Kidney Patients? – National Kidney Foundation, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kidney.org/news-stories/how-much-sodium-safe-kidney-patients

- The role of biological analogies in the theory of the firm (Chapter 14) – Natural Images in Economic Thought – Cambridge University Press, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/natural-images-in-economic-thought/role-of-biological-analogies-in-the-theory-of-the-firm/357C1D5D1A95F1DCCE4A837441E9C956

- Biological metaphor and analogy upon organizational management research within the development of clinical organizational pathology | QScience.com, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.qscience.com/content/journals/10.5339/connect.2016.4?crawler=true

- Disorders of Sodium Balance – CORE Kidney | UCLA Health, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.uclahealth.org/programs/core-kidney/conditions-treated/acid-base-electrolytes/disorders-sodium-balance

- Hyponatremia (low sodium level in the blood) – National Kidney Foundation, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/hyponatremia-low-sodium-level-blood

- Homeostasis (article) | Khan Academy, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/principles-of-physiology/body-structure-and-homeostasis/a/homeostasis

- Hydraulic analogy – Wikipedia, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydraulic_analogy

- Sodium Intake and Chronic Kidney Disease – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7369961/

- Benefits of dietary sodium restriction in the management of chronic kidney disease, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19713840/

- Sodium Intake and Chronic Kidney Disease – PMC, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7369961/

- Significance of hypo- and hypernatremia in chronic kidney disease …, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article/27/3/891/1897873

- Editorial: Renal Regulation of Water and Sodium in Health and Disease – PubMed Central, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9214258/

- Renal Regulation of Water and Sodium in Health and Disease | Frontiers Research Topic, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/20539/renal-regulation-of-water-and-sodium-in-health-and-disease/magazine

- Editorial: Renal Regulation of Water and Sodium in Health and …, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9214258/

- Optimizing Diet to Slow CKD Progression – Frontiers, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.654250/full

- High-Sodium Foods to Limit When You Have Kidney Disease | DaVita, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://davita.com/diet-nutrition/articles/high-sodium-foods-to-limit-when-you-have-kidney-disease/

- Sodium and Chronic Kidney Disease – DaVita, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.davita.com/diet-nutrition/articles/basics/sodium-and-chronic-kidney-disease

- Low Sodium Diet Helps Reduce the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease | Bangkok Hospital Headquarter, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.bangkokhospital.com/en/bangkok/content/prevent-chronic-kidney-disease-by-reducing-salinity

- Renal Diet – NephCure, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://nephcure.org/managing-rkd/diet-and-nutrition/renal-diet/

- Management of severe hyponatremia in a chronic kidney disease …, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.jnephropharmacology.com/PDF/npj-13-e11674.pdf

- Hyponatremia – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470386/

- Hyponatremia – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hyponatremia/symptoms-causes/syc-20373711

- JUNE 2020 – Alinea Nutrition, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.alineanutrition.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sodium-CVD-and-the-J-Shaped-Curve.pdf

- Making Sense of the Science of Sodium – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4420256/

- Salt and hypertension: current views – European Society of Cardiology, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-22/salt-and-hypertension-current-views

- Little-Known Dangers of Restricting Sodium Too Much – Healthline, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/6-dangers-of-sodium-restriction

- A Randomized Trial of Dietary Sodium Restriction in CKD – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3839553/

- No evidence for a J-curve for association between sodium intake and CVD – – PACE-CME, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pace-cme.org/news/no-evidence-for-a-j-curve-for-association-between-sodium-intake-and-cvd/2454016/

- Need for High-Quality Research Methods to Improve Scientific Understanding of the Health Impact of Dietary Sodium | American Journal of Hypertension | Oxford Academic, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/ajh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ajh/hpaf108/8180864

- Association between sodium intakes with the risk of chronic kidney disease: evidence from a meta-analysis, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4723867/

- Association between sodium intakes with the risk of chronic kidney …, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4723867/

- Altered dietary salt intake for people with chronic kidney disease – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8222708/

- A Randomized Trial of Dietary Sodium Restriction in CKD – PMC, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3839553/

- Dietary salt intake in chronic kidney disease. Recent studies and their practical implications, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379373444_Dietary_salt_intake_in_chronic_kidney_disease_Recent_studies_and_their_practical_implications

- High and low sodium intakes are associated with incident chronic kidney disease in patients with normal renal function and hypertension – PubMed, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29198468/

- Sodium intake and renal outcomes: a systematic review – PubMed, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24510182/

- What’s it really like to follow a kidney diet? – Kidney Community …, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kidneycommunitykitchen.ca/dietitians-blog/whats-it-really-like-to-follow-a-kidney-diet/

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD) – Symptoms, causes, treatment | National Kidney Foundation, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/chronic-kidney-disease-ckd

- Do you need to follow a low-sodium diet for your CKD? | PatientsLikeMe, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.patientslikeme.com/blog/low-sodium-diet-for-ckd

- Low Sodium Pocket Guide – NephCure, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://nephcure.org/low-sodium-pocket-guide/

- Kidney Disease Diet & Nutrition, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kfcp.org/learn/treatment/nutrition/

- Diet in Chronic Kidney Disease – Patient.info, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://patient.info/kidney-urinary-tract/chronic-kidney-disease-leaflet/diet-in-chronic-kidney-disease

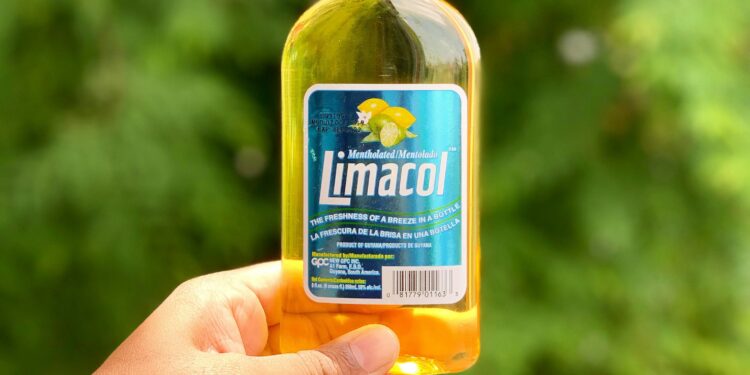

- Caribbean: Sodium and the Kidney Diet, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/caribbean-sodium-and-kidney-diet

- Guide to Low-Sodium Foods for the Kidney Diet | DaVita, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://davita.com/diet-nutrition/articles/guide-to-low-sodium-foods-for-the-kidney-diet/

- Healthy eating for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.kidney.org.uk/healthy-eating-for-people-with-chronic-kidney-disease-ckd

- Katja Hansen, successfully living with CKD | National Kidney …, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://nkfm.org/success-stories/katja-hansen-successfully-living-with-ckd/

- Diet and Nutrition – U.S. Renal Care, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://www.usrenalcare.com/healthy-living/diet-and-nutrition/

- Personalized Nutrition in Chronic Kidney Disease – PubMed, accessed on August 13, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40149623/